“Well I remember the mood of euphoria that gripped the stock market back in the holiday season of year-end 1965,” writes Dick Young in his September 1987 issue of Richard C. Young’s Intelligence Report.

“I had just entered the investment business and was a broker at a Boston based member firm of the New Your Stock Exchange. It was an exciting period. The market had climbed by nearly 50% in a three-year period end 1965, and investors were spending their profits literally before they were booked. It was a period of casino mentality—no one could lose. The party ended with a thud, and the hangover was to last 16 years.”

Why do I bring this up to you in 2017? Because we have just passed the 30-year anniversary of the stock market crash of October 1987.

In his September 1987 issue Dick was writing about dividends and investors yield. Why? Because dividends from stocks are an investors yield—much like interest from bonds, and rents from income property. They are an investor’s friend and are a stranger to the speculator—always looking for a sucker to sell to at a higher price.

Post WWII up to about 1995, dividend yields ranged between 3% and 6.5%. The average was about 4.5%. Those were the days!

When Becky and I graduated from Babson College in 1994, the Dow yielded less than 3% and has been closer to 2% for most of my career since then.

“Investors yield?” Ask any investor today what investors yield is and you’ll see eyes glaze over.

Think about the S&P 500 and imagine the trillions of dollars in perhaps the largest managed pile of stocks in the world as I explain here, here, and here.

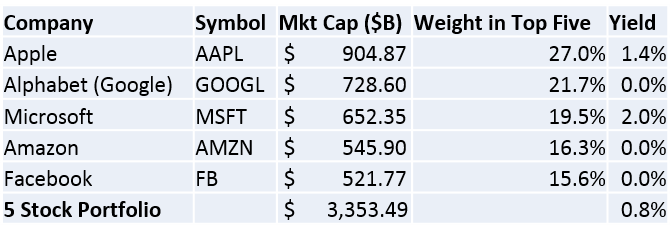

Now, look at three of the top five companies in the S&P 500—they do not pay a dividend—a Blutarsky-like zero-point-zero. And then, take all five of the big guys, and the market-cap weighted investors yield is a whopping 0.8%.

You don’t have to go that far back in time to see the perils of this market’s dismal investors yield. It’s as important as Dick Young’s North Star. and it’s as important today as it was back in the holiday season of year-end 1965.

Is there is a way forward today? Yes.

Dick writes, “At Richard C. Young & Co. Ltd., our goal is to remain balanced as well as fully invested. This repetitive plan, definitely counterintuitive to many investors, ensures never missing the big moves. It also requires never participating in any meaningful way in the bubble or blow-off stage of over-priced markets that are on the precipice of cratering and wiping out a lifetime of savings along the way. No thanks. I long ago learned this bedrock principle.

Today’s investment landscapes and processes have become so difficult that for most individuals going it alone, especially while preparing for a safe and secure retirement, is no longer comforting or attractive. Many of the old standby bastions of investing are no longer an option. I am referring to the vast majority of all-managed equities mutual funds and a wide swathe of the indexing ETF universe. The fund industry has simply outgrown its skin. Funds have grown too big, and their options in dividend-paying common stocks are too few, due to size constraints for massive funds. This is only common sense.

With minor exceptions, I no longer advise these out-of-phase funds. Rather, stocks of individual dividend-paying companies including smaller concerns and foreign securities, are our focus for clients. At our management company, we craft what we label Retirement Compounders portfolios.”

If you see the relevance in Dick’s observations of the yield crisis in 1965, 1987, and 2017, then you need to invest accordingly.

Please email me at ejsmith@yoursurvivalguy.com.

Originally posted at Yoursurvivalguy.com.