UPDATE 9.20.24: At the World Federation of Neurology, Christian H. Nolte discusses a study he recently published in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences on Factor XI inhibitors, writing:

The “holy grail” of preventing and treating thrombosis and thromboembolism would be a drug that was highly effective (preventing clots) and at the same time had a low risk of bleeding. From a hemostasiological perspective, the inhibition of factor XI represents a promising target because a reduced level of factor XI protects against thrombosis without significantly increasing the risk of spontaneous bleeding.

Currently, three different classes of drugs of factor XI-inhibition are tested. These are (1) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), (2) so-called synthetic, small molecules and (3) antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs). This article provides a narrative overview of the current status of studies on all three classes of drugs.

Tests with mAbs have been conducted primarily in DVT prevention after knee replacement surgery. One large phase 3 study is testing the mAbs Abelacimab in patients with atrial fibrillation. The synthetic, small molecules Asundexian and Milvexian are tested in several phase 3 trials, mainly in patients with non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke. Results can be expected in the coming years. Clinical testing of ASOs to inhibit factor XI are still in their infancies.

Read the entire study here.

Originally posted March 22, 2024.

According to Ron Winslow, writing in The Wall Street Journal, several blood thinners are being developed that can help patients prevent the clots that cause heart attacks and strokes without the side effects that have come along with previous blood thinners. Winslow writes:

A new class of anticoagulant drugs on the horizon is taking fresh aim at one of cardiology’s toughest challenges: how to prevent blood clots that cause heart attacks and strokes, without leaving patients at risk of bleeding.

At least a half-dozen experimental blood thinners are in development that inhibit a protein called factor XI, one of several blood factors that regulate how the body forms clots.

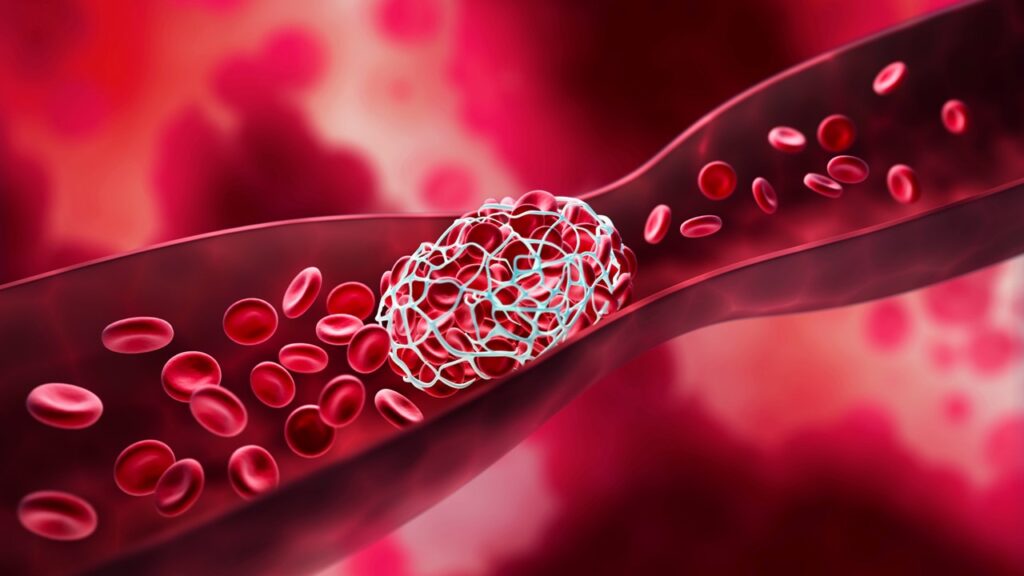

The challenge is this: The body generates two types of clots—good ones that plug holes in blood vessels to stop bleeding caused by external injuries, and bad ones that grow inside arteries and veins. These can block blood flow to critical organs, potentially leading to injury or death.

For decades, drugs developed to prevent the bad clots have targeted proteins involved in forming both types of clots. As a result, preventing clots often comes at the price of a higher risk of bleeding, causing many patients to refuse to take, or stop taking, the medicine.

“Too low of a dose, you clot; too high of a dose, you bleed,” says Dr. Michael Gibson, cardiologist and CEO at the nonprofit Baim Institute for Clinical Research at Harvard Medical School. “Our goal is to keep people from falling off the balance beam. This is what we have been chasing for years.”

Factor XI, it turns out, is crucial for the formation of the bad clots inside blood vessels, what doctors call thrombosis. But researchers now believe that factor XI, unlike other blood factors, plays a minimal role in forming the good clots that stop bleeding. That suggests drugs against it could prevent the bad clots without significantly disrupting the process that causes good clots, and thus minimize excess bleeding associated with anticoagulants and other blood thinners.

Important questions about the effectiveness of factor XI inhibitors have yet to be answered, and success isn’t ensured. Several large-scale or Phase 3 clinical trials are now under way to determine the clinical and economic potential of the new agents. Results are expected later this decade.

At this stage, Factor XI inhibitors “appear to have good safety but maybe not as good efficacy as we would like,” says Richard Kovacs, professor at Indiana University Medical School, Indianapolis, and chief medical officer of the American College of Cardiology, who isn’t involved with the research.

“There isn’t such thing as a free lunch. Maybe that applies here,” he says, adding that more research is needed to determine what role the drugs may play in clinical practice.

A big advance

Any factor XI agent that reaches the market would likely represent an important advance over drugs called factor Xa inhibitors, a blockbuster class of medicines dominated by Eliquis and Xarelto. Since they were approved just over a decade ago, these drugs have supplanted warfarin as the standard-of-care anticoagulant to prevent stroke in patients with the heart-rhythm disorder atrial fibrillation as well as other indications.

Last year alone, Eliquis, marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer, and Xarelto, from Johnson & Johnson and Bayer, racked up combined worldwide sales of about $19 billion. But while the drugs sharply reduce risk of life-threatening and other serious bleeding, including bleeding in the brain, associated with warfarin, patients taking them remain at risk for such side effects as nosebleeds, bleeding gums and gastrointestinal bleeding that can affect their quality of life or even land them in the hospital.

As a result, studies show, an estimated 40% to 60% of atrial-fibrillation patients refuse to take, stop taking or skip doses of the anticoagulants—or their doctors decide not to prescribe them. That leads to more than 50,000 preventable strokes each year in the U.S. alone.

The factor Xa inhibitors “really changed the landscape” for anticoagulation, “but bleeding is still the major complication,” says Jeffery Weitz, a professor and coagulation expert at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, who advises several companies developing factor XI drugs. “If we could have something that is at least as effective and safer, that could take us to the next step.”

Read more here.

If you’re willing to fight for Main Street America, click here to sign up for my free weekly email.