UPDATE 8.15.24: In Valley News, Kate Oden tells the story of another Vermont family-owned farm that is going out of business. She writes:

ROYALTON — A piece of dairy farming history on the Royalton-Sharon town line is in the process of changing hands leaving its future uncertain.

Westlands Farm, a commercial dairy established in 1867, has been on the market for $1.2 million.

A sale is pending, but owner Peggy Ainsworth declined to elaborate this week on who might be buying the farm or the agreed upon purchase price. It’s also unknown to the public what kind of farming — if any — will take place on the property.

On Wednesday, the farm’s herd of 47 pastured Holstein and Brown Swiss milking cows and about 25 younger stock were loaded onto a red livestock trailer. They’ve been sold to Sunset Lake Farm in the Champlain Islands, north of Burlington.

Peggy Ainsworth has been running the farm since the death of her husband, David Ainsworth, five years ago. David, a former Republican state legislator and longtime Royalton town moderator, died in May 2019, after battling kidney disease. He was 64.

Peggy Ainsworth, who grew up in Chelsea, was an elementary school teacher for 30 years. She came to dairy farming 24 years ago when she married David Ainsworth, a fifth generation farmer who grew up at Westlands.

Ainsworth threw herself into the work and loved her time on the farm. “I’ve only been an Ainsworth for 24 years, but it’s special,” she said.

However, she’s ready for retirement. “Let’s face it, I’m 72,” she said. “And I’d rather go out on my terms. I ought to have a few years where I’m not shoveling s—.”

Read more here.

UPDATE 8.18.23: “Make hay while the sun shines.” That old farmer adage has been difficult for Vermont farmers this year who have experienced flooding and near constant rain, preventing them from haying their fields to provide feed for their cows. The lack of hay made on their own farms will force the farmers to buy expensive hay from elsewhere, putting even more farms in financial trouble. The Valley News reports:

In Vermont, of the nearly 200 farms affected by the flooding, one-third cite loss of crop meant for animal feed as the most significant damage, according to a recent survey by the state’s Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets. More than half of the survey respondents expect to experience feed shortage or feed quality issues.

Josh Horan, whose family owns Northeast Corner Farm, where they raise beef cattle in Norwich, needs two straight days of dry weather to eke the moisture out of his hay. That’s been hard to come by this summer.

Hay is often cut multiple times a season on a single field. First cut hay is more fibrous, with thicker grass stems and sometimes containing flowering heads, called tassel. The second cutting is fluffier and greener, with a higher protein content.

Horan is usually done with his first cut around the first of July, but as mid-August approaches this year, he’s still not finished with the initial pass.

He traces the issues with this season’s production back even further than the rain. The late frost that struck the region in late May and froze orchards also might have stymied grass growth.

“I’m not a scientist, but in my observation, the orchard grass, which makes up a lot of the first cut roughage, was way down from the beginning,” Horan said. “I was getting, by volume, less than half of what I usually get.”

There is an art to hay making. To assemble the large, round, wrapped bales of haylage, and especially for the smaller, square bales of dry hay, growers have to pay close attention to the quality of their soil and the weeds getting into the pastures.

“And the thing that we would like to be able to control is exactly when we’d be able to harvest everything,” Horan said. “The nutrition is optimal at a certain point, and if the weather’s not cooperating, it’s a problem.”

UPDATE 6.29.23: Vermont’s farmers are not alone in facing tough times. Agricultural economists surveyed by the University of Missouri and Farm Journal are worried that the financial health of U.S. farmers will continue to decline over the next year. Prices for production are expected to remain high, while prices for crops are expected to drift lower. In Dairy Herd Management, Tyne Morgan reports on the highlights of the survey:

- The perceived financial health of U.S. agriculture is trending lower and is expected to continue to decline over the next 12 months.

- Production costs, global competition, geopolitical risks, drought and demand headwinds are among the main drivers.

- The majority of agricultural economists expect farm income to drift lower, with some expecting levels to land closer to the five-year average in 2024.

- High production expenses are the biggest obstacle in 2023.

- 2023 crop yield estimates vary widely among the economists surveyed.

- Economists expect crop prices to drift lower in 2023 and 2024.

- Beef cow supplies are forecast to continue to decline this year.

Farmers facing the troubling economics of Joe Biden’s America should consider the methods and techniques used by America’s food kings, Joel Salatin and Alfie Oakes, both in production and distribution.

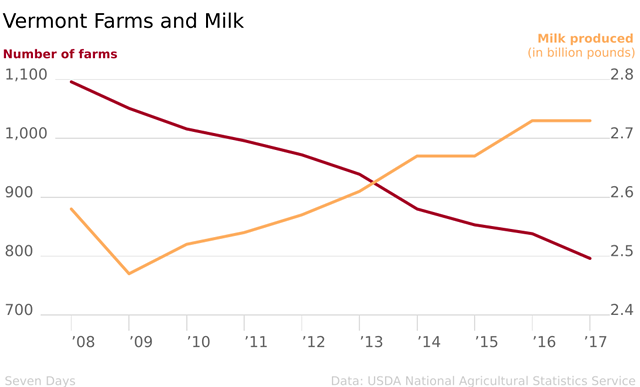

UPDATE 6.21.23: In Seven Days Vermont, Kirk Kardashian explains the consolidation in Vermont’s dairy farming industry and how it’s affecting small farmers like Robert Bassett from Woodstock. Kardashian writes:

Five years or so ago, dairy farming stopped being fun for Robert Bassett.

He had taken pleasure for 30 years in managing his herd, working outdoors and being his own boss. He had chosen this life, dropping out of college, abandoning his plans to become an engineer, and returning to the 98 acres his grandfather and father had farmed since 1945. The Bassett Farm was a landscape of flat pastures, hillside forest, red barns and Jersey cows less than two miles from the Woodstock Village Green. He felt a deep connection to the land.

For three decades, Bassett rode the steep ups and downs in milk prices and found ways to manage rising costs. He held on when the family’s 240-year-old farmhouse burned to the ground.

But a persistent oversupply of milk in the U.S. depressed prices paid to farmers so much, for so long, that most dairies like his hadn’t seen positive balance sheets in years. Bassett, 55, was growing weary of toiling for such little return. His 100-cow farm was just too small to operate with the same efficiency as the emerging 1,000-cow dairies in Vermont, and he couldn’t afford to expand.

So, last fall, Bassett sold his herd. He is trying to figure out what to do next. For the first time in more than 75 years, no Bassett is milking cows in Woodstock. In fact, few people are. Bassett’s farm was the last remaining dairy in town, aside from the nonprofit Billings Farm & Museum.

As he sat at his kitchen table one April morning and reflected on the state of the dairy industry in Vermont, Bassett offered a simple thesis.

“There’s no money in it,” he said. “You’ve got to get big or get out.”

Many have gotten out. The business that shaped Vermont’s landscape for more than 150 years has been largely transformed into an industry that a 1950 hill farmer would not recognize.

That year, Vermont was home to 11,000 dairy farms. Today, there are 508. Because what farmers are paid for milk rarely covers what it cost them to produce it, they search for economies of scale — to milk more and more cows and spread the expenses over the larger revenue. From 2012 to 2022, that resulted in a 44 percent decrease in the number of small Vermont farms, defined as those with fewer than 200 cows.

Others, as Bassett noted, got big. Even as the number of dairy farms overall declined, those with 700-plus cows more than doubled, to 35.

What hasn’t changed significantly is how much milk Vermont dairy farms produce. Despite the industry’s much publicized economic problems, it still generates a staggering 2.5 billion pounds of milk a year, or roughly 300 million gallons. Dairy farmers spend $500 million annually for goods and services and accounted for 6,000 to 7,000 jobs in the state, the Vermont Agency of Commerce and Community Development found in 2015.

Read much more from Kardashian here.

Originally posted August 13, 2018.

On a recent road trip into Quebec, Debbie and I drove beautiful Rt. 100 from near the southern border of Vermont to its termination near the Canadian border.

By the time we were into Vermont’s Mad River Valley, it occurred to us that that we’d seen nary a cow. Remember, wait till the cows come home? Well, no longer in Vermont. And those thousands of iconic old barns? Decaying and abandoned, the majority with not even a for sale sign as a memory, never to be inhabited by Vermont dairy farmers again.

In the past year, 61 Vermont cow dairies have ceased operation, leaving the state with just 749, according to the Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets. That’s down nearly one-third – from 1,091 a decade ago and from more than 11,200 in the 1940s

Tony Kitsos, the UVM Extension outreach specialist, explains that new manure pits and runoff controls are sometimes “the last straw” for dairies.

That doesn’t bother Michael Colby, an agricultural activist from Walden, who cofounded the advocacy group Regeneration Vermont.

“The dairy model is dead. We need to come to grips with that,” he said. “This model’s not working for the farmers. It’s not working for the cows. And it’s not working for rural communities, which are being hollowed out. The only ones benefiting are big ag and big dairy.”

Colby takes particular issue with large-scale farms that rely on genetically modified feed and antibiotics to enhance milk production in sedentary cows. The resulting waste, he argues, is a “disposal nightmare.”

Indeed, a new study released last week by UVM found that annual milk production increased from 5,000 to 20,000 pounds per cow between 1925 and 2012. In that same period, livestock density jumped by 250 percent as farms increased in size, consolidated their operations and kept their cows confined in barns.

Colby believes the solution is grass-fed, organic milking operations. But while a quarter of Vermont dairies have gone organic, even that market has tanked in the past year, as supply has outstripped demand.

The way Colby sees it, Large Farm Operations — defined by the state as those with 700 or more cows — have no place in Vermont.

“I don’t think there is a humane or environmentally sustainable way to operate a dairy LFO,” he said. “It’s constant confinement — and that can’t be done humanely.”

Read more here.

Originally posted August 13, 2018.

If you’re willing to fight for Main Street America, click here to sign up for my free weekly email.